Interview by Joe Delon, May 7th 2021

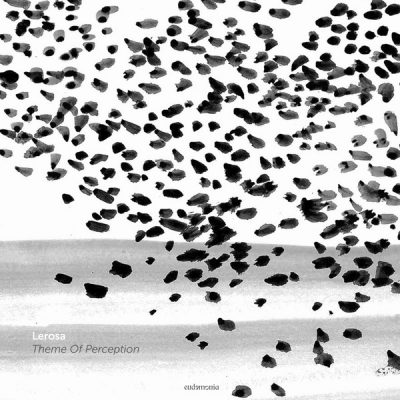

This instalment of our mix series comes from the DJ and prolific producer Lerosa. Leo spent his early years dancing and playing in the clubs of late 80s Rome before moving to Dublin, where he has lived ever since. In the early 2000s he began releasing records on respected labels like D1 and Uzuri, establishing early on a reputation for finding elegance in simplicity. In 2009, I had the pleasure of seeing Leo play a liveset in Fabric room 1, while a decade later he DJed at the 2019 edition of Lisb-ON festival here in Portugal.

Since the first lockdown in early 2020, Leo’s life has revolved around making music, interrupted only by his day job and his two cats demanding to be let in and out of the window of his home studio in Killester. Recent releases – including his Kiss Me Again EP for Welt Discos – show his love for italo, dub and Giallo soundtracks (among others), as do the clips he uploads almost daily to his Instagram.

Leo’s mix focusses on a selection of studio producers he’s been following closely, be it for the final sounds they achieve or the methods they use along the way. Our discussion of these producers became a jumping off point for a broader conversation about the creative process and what it means to be an artist – the challenges, the joys, the insecurities and how, in the end, the best approach is to simply carry on ‘doing’.

The first track by Spacetime Continuum is the only one I recognised in the mix. It’s one of my all-time favourites.

I haven’t really bought new records in a while so I tend to think my collection is quite obvious, but then I remember I do have 5,000 records! In the mix they’re all different producers that I’ve always looked up to. Some of them are actually very recent, but still I find them very inspiring.

Spacetime Continuum, anything from Source or Reflective, Move D back when he wasn’t doing house. I love all of that. I thought it’d be a good encapsulation of all of those sounds. I was thinking of putting another thing that was less obvious from Source, Sad Rockets, an album I found in Germany that came out in the 90s. It’s more like a guy with actual drums and Rhodes, it’s a sort of post-rock if you will, but it’s really nice. Really slow, really stoned.

The second track by Hawk is a bit like that, live guitar and a drum machine.

It’s a dude with a guitar but he has a good ear for drum machines. He gets these very basic accompaniments going and then it’s just him playing guitar over the top. He does it in a way that’s very cinematic. It’s kind of kraut-rocky. Some of them have got that Tangerine Dream sound. I like it because it introduces something into the studio which a lot of producers don’t have: that fluidity, where you’re just improvising with no MIDI, no computer. That’s something I try to do now. Make a very basic loop, I have one synthesiser like the Abyss that has a really nice sound, then just jam on it freehand for 10-15 minutes, then chop it up.

How does that process work? How do you preserve the flow of what you’ve done live when you chop it up?

You try to get to a logical point in the phrasing. There are points where you can literally put a stop, then you listen and think, “OK, does this sound good?” You’d be surprised how often it does.

If you read about the guy who used to record Miles Davis, Teo Macero, he explains that the tracks you hear on a Miles Davis album are not what happened in the studio. They would be jams with all these guys in the room going for 15-20 minutes. Back then they’d have everything on tape, so you’d make a copy, find the spot where you could do an edit, and blend them very quickly between the two tape players. The concept is the same.

In the Hawk track there are moments where the bass really shifts quite dramatically, which sounds a bit more pre-planned or engineered.

It’s hard to know. It could be that he had a change pre-programmed in the machines. Maybe he has something that he can trigger with his arm or his foot, if he has a controller, to change the loop. That’s the beauty of this kind of production – a lot of movement, changes of keys. I’m not really good at changing keys. The guys who come from music and playing with other musicians, they have fewer problems. Even today when I was doing this Grimes cover [of ‘Oblivion’], it’s just two chords, but at the beginning I was thinking, “Oh how do I do this?”

That track later in the mix by Billy Ray de la Haye – great name! – has a similar flowiness. It’s quite lo-fi and he’s just letting things roll on. He’s playing keys, and you can hear they’re not sequenced, they’re just played by hand. He’s a bit like Legowelt but too loose and messy for Legowelt, a bit of a krautrock-y vibe. I was going to remix one of his tracks, and when he sent it to me I thought, “This is such a nice track. I’m going to destroy it!” It was similar to the Hawk thing, these careening, beautiful synths… A bit like Beautiful Swimmers. Psychedelic. I like it a lot, but I find it very hard to do, I’m very rigid in my thinking. It’s hard when you have all these machines based on a grid to achieve that flow.

This whole mix is full of productions that are looser, more shifting, not played on a grid pattern, like the Moody Boyz one – not imprecise, but definitely not rigid.

I think it’s a dub version. Tony Thorpe. He was in there at the time of early acid house and on this EP there’s a version by the Black Dog, back when they were doing their early stuff on Warp. He was very low-key, but involved with everyone. The Orb. Most of the Londoners I speak to, when you say Tony Thorpe, if they’re of a certain vintage they’ll nod approvingly.

He’s quite well versed in the studio. You can hear he’s very technical, old-school. One of those people who maybe came from working in the studio in the daytime. Some of the stuff is quite poppy, very clean and very professional for the time. It wasn’t just a drum machine and a synthesiser. If you listen to that one properly there’s a lot of really nice synths for the time – M1s, Korgs – expensive stuff back then. Now no one wants these flagship workstations but back then they would have been two or three grand in the studio, and would have been what pop hits were made on.

It’s not just the machines is it, it’s also the process and the way the sound is mixed?

Some of these guys, like early The Orb stuff when they had another guy doing the engineering, they were all engineer heads. You can hear they know extra bits of the process. Nowadays you can have everything in your computer, but just because it’s there doesn’t mean you know what to do with it. You still need to have a background that tells you how to do ducking, how to achieve certain qualities of sound with a flanger instead of a chorus. You can just mess about and get results, but if you’re an engineer you can be a lot more focussed. It doesn’t mean you’re a better artist, but you can hear the shift in production skills in some of these records.

I don’t like very clean productions. A lot of these guys are very dirty and low-fi, they just have the basic grounding and then they try to get extra energy from running things too hot, too loud, getting a bit of distortion. Some producers have a much cleaner style, like Anthony Rother. His early electro was really good but on his Instagram now everything is so clean. His studio is spotless like a surgery room. From a punter’s point of view, once you’ve listened to a couple of Anthony Rother records you’ve heard them all. I don’t think that’s a good thing. Whereas Tony Thorpe can do an EP like this one, which sounds all kind of jungle-y, break-y and lush pads and weird samples, and then he can switch and make a really basic 303 acid track. So he has range.

When I listen to my own stuff I can see patterns, maybe I’ve done the same electro track in different flavours. It’s a concern because I don’t want to repeat myself. Then there are a lot of artists who just stop. I don’t think $tinkworx has released anything in ages.

Jamal Moss seems to release something practically every month!

He’s very inspiring. A lot of his later production is done just on an iPad, running this very run-of-the-mill production tool made by Korg, which they’ve filled with very basic drum machines and synths. So the way he does it, he has 25 of these things, and literally his track is him bringing up and down all these little patterns he’s created in the virtual mixer with his fingers. You can watch him playing in Rush Hour – he was there with two iPads and a little delay effect. There’s no sync, they’re not synced or anything. Just this one then that one, and he has loads of them. The ingenuity in it is outstanding. Especially in a time when a lot of artists don’t get near that. They need to spend 60 grand on a modular rack, or they need 25 synths. This guy’s here with his iPads running rings around a lot of producers with the sheer creativity of it. It’s a humbling experience.

This is a guy who’s massive worldwide and he’s making his tracks on an iPad, and they’re all overdriven to fuck! And all these guys are saying, “Oh, he’s using tape! He’s using this really rare analogue mixer and it sounds amazing cos he’s doing the thing with the tape!” No he’s not! He’s just using a shitty mixer, but he’s got so many ideas in his head that he’s just pushing them. It’s a really interesting way of working, just having this one app and getting really stuck into it.

He’s released a million things but he does keep on changing. Then he started playing the sax, one of these electronic saxes, where you blow in it and it translates the blowing into the equivalent of what a sax would sound like, but he’s plugging it into something else. Then he recruits all these jazz cats from Chicago and does an ensemble. I wouldn’t have the balls to call up some jazz musicians and ask them to improvise with me.

I could have played any old track of his. I have loads. At the start I was buying everything. I was really excited, the way I was excited about Carl Craig. I’m always worried when they start getting the jazz guys or the orchestras. Especially the Detroit guys when they get the orchestras, it’s never a good sign. The new Floating Points and Pharoah Sanders thing [recorded with the London Symphony Orchestra] sounds good, but then they’re both jazz guys. It doesn’t sound like ‘The Bells’ but with a philharmonic orchestra on top. No! Don’t do that! It’s wrong!

Have you experimented with bringing live instruments into the studio?

I went through a phase where I was making a lot of dub tracks, trying to learn electric bass and recording instruments. I bought these rattlers and shakers. I was doing dub more in like a post-punk thing with synths. I was thinking of Sly & Robbie in the Bahamas in Island Studios doing the classics. That’s where all the famous records of the early 80s were coming from, the Island Studios where they had all these session players, so you’d have a lot of electronic stuff and a lot of musicians together. I did a lot of those maybe two years ago. And now and then the odd one pops up, but I think they come out better if I just keep them electronic rather than getting too carried away with the tambourines. You have to be careful because then the bongos come out, and when the bongos come out… I had this mad electronic bongo, a great sounding piece of kit, but I sold it. Probably for the best.

Occasionally I feel the dub thing coming and I’ll just record something. They’re really nice to do – there’s so little in them, but you have to work a lot. You can hear in that Weatherall track, it’s just a basic rhythm and a basic bassline, but then all those little ‘drr-drr-drr’ breaks and restarts and the pings, and if you listen to it every time the ping is different. So you might have a very long session that you’re chopping down, and then you have to have the variation.

How do you know when to stop changing or adding things? There’s a virtue in simplicity.

Every producer dealing with house and techno would say that they struggle with this variation, how are you going to keep in interesting? There are all sorts of ways to develop what would make a track interesting. Some people don’t do anything. Basic Channel defined that thing where there’s very little change and yes it’s very engaging. Early Theo Parrish, very long and very few changes.

I’m studying that and these producers. I like things where I don’t have to do too much. I have to understand whether it’s because I’m lazy and I’m not putting the weight in, or because I’m careful. Because you can do too much, and then the track loses something. If you start adding too much, it gets too busy. It’s a fine art to find that balance. All these producers in this mix, in one way or another, have found that balance.

You mentioned the tune by Andrew Weatherall.

That record is quite recent, I think it’s one of the last 12s that came out with very little fanfare. After all these years he goes and drops a little underground EP like that. It just sounds great! It’s very basic but at the same time there’s a lot of breaks and surprises. The thing with him that I always liked was that, for years, no matter what, he could just put out a record and you’d go, “Oh, that’s interesting!” There again: range.

He gets the dub thing, he’s respectful of where dub is, which is the bassline, big skanky rhythm, and all the pings – all these little machines that make ping noises. He just captures the essence, the ‘rules’ of dub. I was really upset when he passed. It’s good to have these older guys with integrity and who can still put out a record like that, and be taken seriously. They don’t have to get the orchestra out or a big collaboration with whoever. It was just him and another fella in a studio smoking spliffs and putting out this amazing stuff.

Jockey Slut put out a tribute booklet with the money going to his family. It was interesting to read his entire career trajectory. As a teenager he started out at the highest level, but he didn’t capitalise on it because he couldn’t be arsed to embrace all that stuff. He just worked hard at being a good DJ and a good producer. That’s what I always liked about him. I see myself in that obviously, a reluctance.

You feel reluctant about the ‘industry’ aspects of making and releasing music?

I look at some people and wish I was better at it. This is why I leech off talented label owners who have the necessary get up and go that I lack. It really strikes me when artists have those skills. I do have them too in some areas – I have a job and a house! – but for music it’s something that eludes me completely. There’s a bit of laziness.

You don’t have to do it either.

Yeah, at this stage what’s the motivation? I could open a bandcamp and sell a few t-shirts. If my music wasn’t available then I’d have a reason. But I like this thing of interacting with a label, and that remix with Marco would never have happened if I was releasing my own music. But if you interact with other people who have a different approach, they might suggest it. It does have its ups.

It’s also that kind of insecurity and impostor syndrome. You think you don’t have the right skills to do the job properly. Do you follow Luke Unabomber? He’s very funny, because he very much talks about this constant talking yourself down that you do. He really struggles with it and he talks about it, he tries to work it out. It’s quite common. You just think you’re shit. It’s a relentless thing that we all do. It’s a mental health thing. Especially when you do art, though also people in other fields. You’re working in an office and you get to a certain age and you look at your life and say ‘what am I doing?’

Art maybe makes you particularly vulnerable to those thought patterns because it’s such a personal form of expression.

It’s really hard because nowadays with music, this music, there’s some people that make careers out of it but there’s thousands of people who just get a couple gigs… You feel this pressure that you’re supposed to be places. I see that with young people who just come on and have everything all organised, maybe they have an EP out and they have a photo shoot, a bandcamp, merch, everything. There’s an enormous amount of pressure, because there’s so much competition. They have these reference points, high-achieving stars, ‘that’s what I’m supposed to be like’. Then you get this unrealistic…

I look at people who have done a lot like me, then there are people with a higher level of recognition, and you think you’re doing it wrong. You’re doubting yourself, you’re not remembering that actually you do this because you like it. I like being in the studio. It beats doing a lot of other stuff that I could be doing. Thankfully at the moment there’s nothing else I could be doing, because everything is closed, so it’s great. But when I could have been nurturing my relationships, I was doing this. It also means this is what I -really- like doing.

I get the impression making music can be quite a therapeutic process when you’re deep into it. It brings you into the present, doing things ‘in the moment’.

That’s important for me. I like doing. In general I have this thing of just recording and moving on. Sometimes I get an idea and explore it over two tracks, but then I get bored and do something different. It depends on the day really. The clips on IG are a kind of diary, showing what I’m feeling. All this stuff is very felt.

I know it sounds a bit cheesy, but sometimes it’s a very emotional thing, especially when I’m mixing things down. I tend to do everything at the same time, so when I’m recording a final take, if it’s good, I tend to have a strong emotional attachment to the track. I don’t want to say ‘oh when I recorded this I was very emotional’, I hate that! Everyone will attach their own thing to it, whatever it makes them feel. But a lot of this stuff I do I tend to get emotional.

Those are the moments where I’m reminded why it’s important to do this. Where else do I have these cathartic moments? I sound like Madonna talking, cheesy, but that’s what it’s like. Sometimes I’m in this thing where I get really lost. Even when I was making the Grimes cover, once I hit the right thing I was really [bops] pulling shapes in the studio. ‘This is fucking it!’ Really lost in it, sober as a judge.

Then sometimes I do a track I don’t like or I can’t finish in the studio, I go downstairs and I have a shit evening. I spend all night thinking ‘Is that the best I could do with that?’ and then the following day I go back to it. It’s stupid! Even if they get released it probably won’t be for another five years! I will have forgotten all about it.

This is a challenge I see for producers who are often at the mercy of label schedules, never mind prevailing trends. Especially if the music will be pressed on vinyl. It must be hard to focus on ‘doing’ and finishing things when the pay-off/job satisfaction is so delayed from the act of making.

I remember reading this interview with Anthony ‘Shake’ Shakir, years ago, where he was saying “I make a lot of music. I’ll make a track, maybe you don’t like it, but I’ll make another one. And if you don’t like that one, then I’ll make another one, and you might like that one.” He was just very humble about it, just saying “I’m going to keep on doing them anyway – this might not do it for you, but…”

From the start that’s how I’ve worked. Recording everything. A lot of this stuff I don’t necessarily like. For example, ‘Karnak’, I wasn’t really sure about it, but when I put the clips up, I noticed other people liked it. Then when you put that link up recently of the DJ playing it [Rubi @ The MUDD Show], I thought “Oh! That’s a nice track.

But you see that’s why you need to work with a label, it’s important. You need that detachment. I might not hear something special, but a year and a half down the line when someone else hears it it’ll make sense to me. A lot of the stuff that’s been released I didn’t feel it was that strong until a year or two later, and then I go “Oh! OK.”

You can’t trust your own ear, that’s why I record everything. You can spend your whole time waiting for the perfect thing, like some producers who really struggle with that. They don’t record anything, or it takes them three months to do a track, with everything planned and perfect. To me that’s a recipe for madness. Spending three months on a track… I get really nervous if I’ve spent more than two days.

The feeling of rejection might be amplified too, if someone’s put so much into it and then don’t get the response they hoped for.

That’s why I approach remixes in the way I do. I always send them a couple of remixes, two versions, cos in the time it takes me to do one remix most people wouldn’t even get started. I can do one in a couple of days. So I send a few and say ‘if you don’t like them, you don’t have to pay’.

What’s it been like when you’ve had your own tracks remixed? How many have there been?

Not that many actually.

I remember the Elbee Bad remix on Uzuri.

Oh yeah! It was him that approached us. The Elbee Bad! He heard the original of ‘Metaphor’ and he went to Lerato and said “this track really nails that NYC thing, I really want to do a remix of it.” He volunteered the whole thing, just out of the blue, and he made that remix. And it was a really nice remix. I really like the spirit of it, this oldschool NYC legend listening to it and saying “This is the shit, I’m going to do a remix.”

I like Marco’s remix of your track towards the end of your mix

I really love that one. You know, you’re kind of scared. It was something organised by Lunar Disko. I love Passarani, I have loads of his stuff. I never met him, but we started chatting. He’s from Rome, so he’s like an old friend from your home town. In Rome, there was a record shop that he used to own, and I was buying records there when I was a teenager, though I didn’t know it was owned by him. Lunar Disko pushed this thing and I was a bit concerned, you never know… What if a legend of yours does a remix and you don’t like it?

But in fact I was like, “Shit! Look at this guy. He takes my track, makes it a lot better, and there are key changes everywhere. And they’re great key changes!” He makes all this mad shit with the studio where he does different breaks, and this new theme at the start. Then I really like towards the end where he put the 303 and there’s these kind of angelic voice parts. I said to him, “Marco, do me a nine minute version with the 303 and angels!” And he said – and this is such a Roman thing – “I only put the 303 in the last two minutes so people will go ‘Oh fuck,’ because I wanted to represent the unfairness of life.” And that’s such a Roman thing to say! In Italy, there’s this thing where life is just hard, and it’s unfair, and you just have to put up with it. It sucks and that’s it. And he really meant it! He’s pushed everything to the max in the track – breaks, key changes, these really nice pads, it has everything. So he didn’t make it too busy. He just put the 303 in at the end. I was delighted.

These Italian guys all seem to be very proficient in the studio. I put the other guy before Marco [Valerio Delphi, the other half of Tiger & Woods] who has that sound I really associate with Pigna. It has that beautiful, simple, melodic loop. Then there’s Raiders Of The Lost ARP.

And then you finish the mix with a remix that you did. I like it because it feels like a sort of closing statement that brings together many of the sounds from the rest of the mix, and some of the attitude.

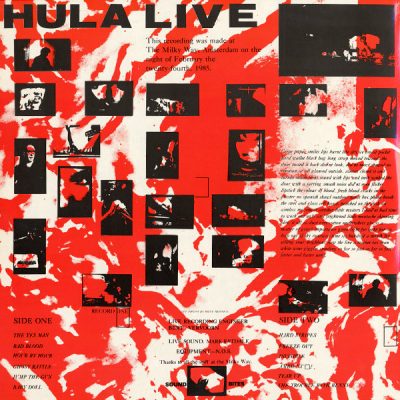

That remix happened at the time I was doing a lot of that dub stuff. But I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to do more like those kind of English bands, Hula out of Sheffield, they were cool. They were kind of like early Cure stuff, kind of new wave. Sort of industrial, with very dark bass and heavy drums. If you catch videos of these bands in the 80s they’re always playing with no tops, black leather pants, mad fucking hair. Just playing these huge drums, really satisfying-looking. They were mostly English, and they would be post-rock, post-punk. I was going for that kind of vibe. It was just again another progression, I was doing the study of anything post-punk, two years ago I was really fixated on all this post-disco or no-wave or whatever you want to call it.

It’s like you’re slowly turning yourself into a one-man-band who can play all these different genres.

A lot of these things I do is a learning exercise. Cos maybe I want to learn how to do something in particular. Even just doing the cover of Grimes was about reminding myself how to do this or that musically. I’ve spent a lot of lockdown time thinking about these guys who seem to refine… For example in French Cuisine in the 1980s, it was just constant refinement and refinement, until the dish you’re getting is a distillation of a tiny little thing. People who manage to do something new in the 21st century, it really takes some balls, cos surely everything is done now, with the internet and everything.

There was an article where Grimes was saying that she was born in the 80s, so the internet was there from the start. Kids now if they want to listen to dnb or post punk, it’s all there, you can experience it simultaneously. She was listening to Aphex Twin and chamber music quartets and grew up with it all together. It must be a really odd way to come of age.

When you’re a listener that’s interesting, but when you’re a producer what do you do? What’s the point of doing anything because everything from the past and present is there simultaneously? You have to have a different frame of mind, and you can spend a lot of time thinking about it. But actually you should just do it, whatever comes to you. If it’s disco, so be it, if it’s drum machines, so be it. At this point… Dozzy’s new thing sounds like drum and bass, really. I heard a snippet, it’s like 160bpm madness, bleeps and drums. It’s great.

Tracklist

Spacetime Continuum – Fluresence [Reflective]

Circuit, Burns & Hawk – Track 2 [Not On Label]

$tinkworx- Mi Casa [Bunker]

Andrew Weatherall – Kiyadub 45 [ByrdOut]

The Moody Boyz – July [Guerrilla]

Hieroglyphic Being – A Time Warp Synthesizer [Mathematics]

O. Xander – Dirac Sea [Nous]

Billy Ray de la Haye – Orpheus [Tabernacle]

Valerio Delphi – The River [Final Frontier/Pigna]

Lerosa – Ummon (Passarani Remix) [Lunar Disko]

Moon – Appeal (Lerosa Remix) [Frank Music]

Follow Lerosa on Soundcloud / Instagram

Check out Leo’s records at our Webshop